A lemmatization guide for medievalists

Table of contents

Contributors:

- Eliana Magnani

- Nicolas Perreaux

- Ariane Pinche

- Thibault Clérice

- Philippe Verkerk

What is lemmatization?

Lemmatization is the reverse process of inflection (declension or conjugation). It associates with a lemma (a dictionary entry) all the inflected forms that come from it. These are the declension forms for a noun or adjective, and the conjugation forms for a verb. Lemmatization therefore consists in assigning a lemma to an inflected form. In addition to the flexion itself, there can be graphic variations for the same form. An inflected form is sometimes called a “lexeme”.

In the case of inflectional languages with high graphic variation, such as those used in the medieval West - Latin and vernacular languages - the development of formalized, computer-aided search procedures involves lemmatizing the texts used. This process - whether manual, semi-automated or automated - is nothing new, but in recent years several lemmatizers or parameters for lemmatizing medieval languages have been created.

What for?

Lemmatization is part of the field of automatic natural language processing (NLP). It is a prerequisite for various types of textual corpus analysis and text/data mining, whether philological or historical.

Lemmatizing and annotating the morphosyntax of a corpus then enables it to be interrogated for sorting or statistical analysis, operations that are often just as necessary for the linguist, the scientific editor or the historian. For example, from a lemmatized corpus, it’s easy to compile a glossary listing all the graphic variations of a word under a single entry, by sorting on the basis of the annotation lemma, which is unique for each word in the lexicon.

Syntactic analysis of an extended corpus is also possible to detect certain dialectal features. For example, in Old Picard, the feminine personal object pronoun is sometimes spelled le like the masculine pronoun, instead of la. Morphosyntactic annotation can then be used to quickly calculate the statistics for the appearance of this phenomenon in texts, in order to date it or determine the territories where it is most frequent. At text level, these calculations enable the editor to determine whether or not the phenomenon is marginal to his corpus, and to decide whether to correct or retain the spelling in his edition by determining whether it is a dialectal trait or a copying error.

Applied to a diachronic textual corpus, relating to a precise spatial entity (a region, for example) or grouping together several such entities (all the regions of Western Europe, for example), lemmatization makes it possible to analyze it from the point of view of the constitution and evolution of semantic fields, and thus nourish historical interpretations. The frequency of a word, its association with other terms - co-occurrences - and their distribution in chronology and in different spaces, are all elements that can be subjected to empirical observation and statistical analysis. It is then possible to evaluate lexical and semantic changes by correlating them with other contemporary historical phenomena, to situate unknown linguistic and semantic innovations in time and space, or to discover unexpected lexical associations.

Which tools?

From a technical point of view, automatic or semi-automatic lemmatization involves a number of operations. These operations take place after the acquisition of the text(s) in an elementary digitized format (either through an already available file, or through manual input, or through an OCR/HTR process). The main stages in the lemmatization process are tokenization, i.e. the breakdown of the text by lexeme, during which the text can be pre-formatted according to the choices and needs of the tool designers (e.g. cleaning up of special characters, separation of enclitics); morphosyntactic tagging of forms (POS tagging = part-of-speech tagging) with a set of tags that varies widely from one tool to another; and the grouping of forms under the corresponding lemma. There are a number of difficulties to be overcome in this process, including homograph disambiguation and graphical variation of forms.

Current tools for associating a correct label (POS) with forms fall into two main groups.

The first use probabilistic taggers based on a predefined lexicon and rules, combined or not with successive training to improve pattern and lemma recognition (e.g. TreeTagger with parameters for medieval Latin OMNIA).

The latter are based on more recent technologies known as “neural networks” (or deep learning), algorithms which, starting from a pre-annotated corpus (or training corpus), aim to teach the application to create lemmas which do not appear in the training corpus, according to their semantic representation (co-occurring words) (e.g. Pie, Hydra).

In both cases, manual work is required upstream, either to establish a lexicon and rules, or to annotate a corpus. Downstream, too, manual intervention is required in both cases to correct the corpora annotated by the lemmatizers.

Where to start?

Lemmatization comprises several main stages:

- The acquisition of the digitized text (or corpus of texts) is a prerequisite for lemmatization. This can be done in a number of ways: using pre-existing files, manual input, or using automatic optical character recognition (OCR - Optical Character Recognition) or handwriting recognition (HTR - Handwritten Text Recognition).

- The preparation of files consists, on the one hand, in saving them with UTF-8 encoding and in .TXT in general, and on the other hand, in the post-correction process, particularly for texts acquired by OCR or HTR.

- This is not necessarily linked to lemmatization, but when building up a corpus of texts, you need to think about the preparation of metadata, which is usually contained in a .CSV file. Metadata includes file names and dates.

- Tokenization consists of the desired formatting of the text (standardization of spelling, separation or not of enclitics, etc.), its division by lexeme, a word or a punctuation mark per line. Tokenization is optional and may or may not be included in the tools.

- Actual lemmatization involves morphosyntactic tagging of forms (POS-tagging = part-of-speech tagging), i.e. assigning a POS to each token (noun, adjective, preposition, conjunction, punctuation, etc., whether or not associated with mode, case or number). Label sets vary from one tool to another: 9 labels for Medieval Latin in OMNIA, 91 labels for Classical Latin in Collatinus, for example. The lemma for each form is usually assigned after the POS.

- Recomposition of files, with tokens, lemmas and metadata.

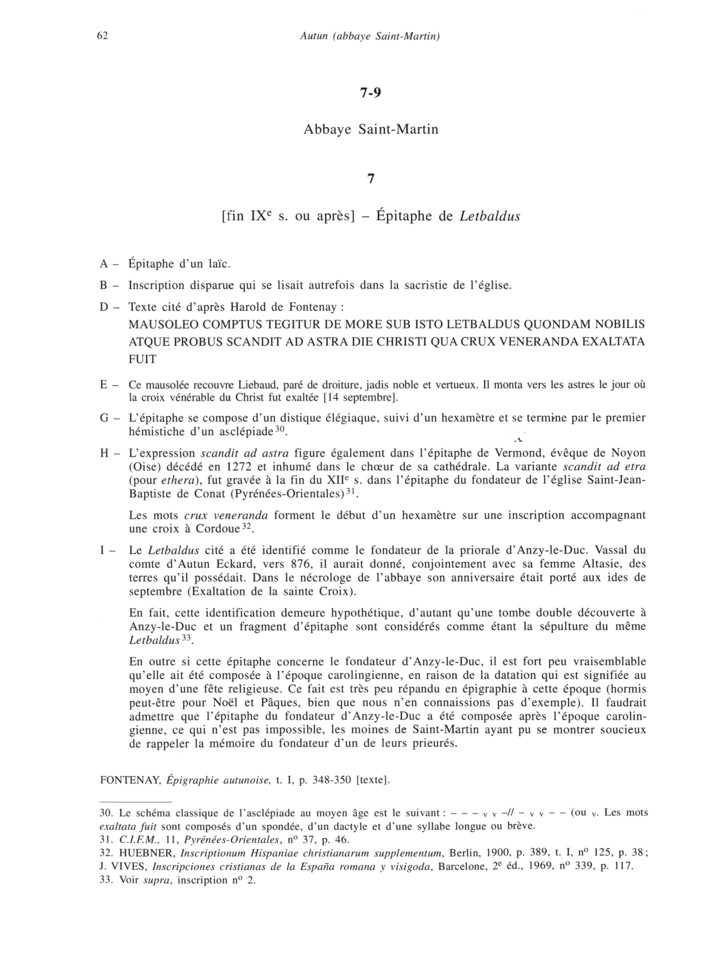

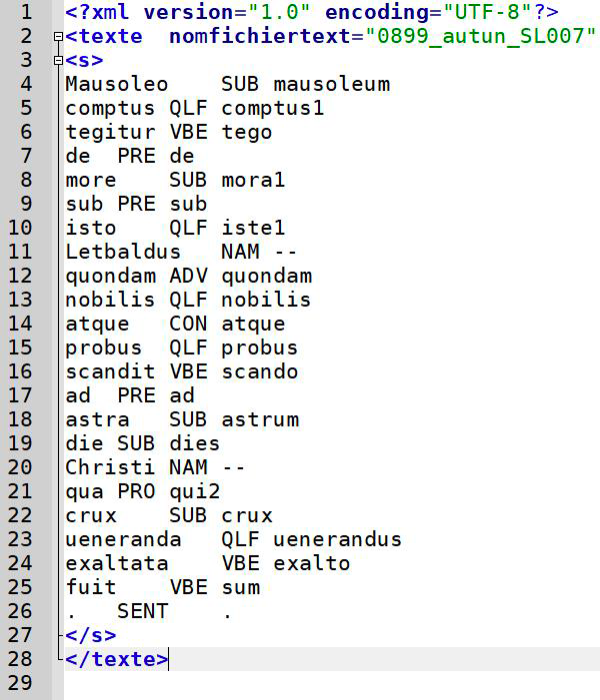

Here’s an example of the processing of an inscription from the Abbey of Saint-Martin in Autun, dating from the end of the 9th century, the epitaph of Letbaldus:

- Acquisition of digitized text from the digitized edition available on the Persée platform. Corpus des Inscriptions de la France Médiévale, vol. 19 : Jura, Nièvre, Saône-et-Loire, éd. R. Favreau, J. Michaud et B. Mora, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 1997, p. 62, n° 7 (https://www.persee.fr/doc/cifm_0000-0000_1997_cat_19_1).

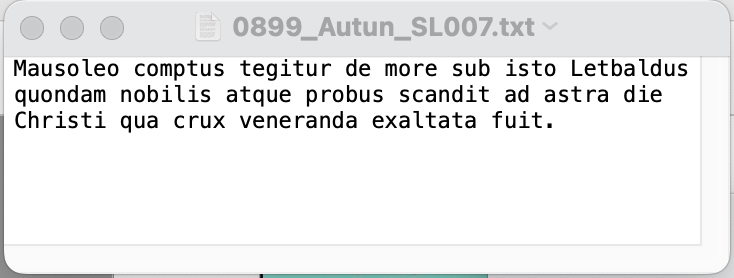

- Text encoded in UTF-8, saved as .TXT, with simplified metadata elements in the file title (Date, Place, Edition reference).

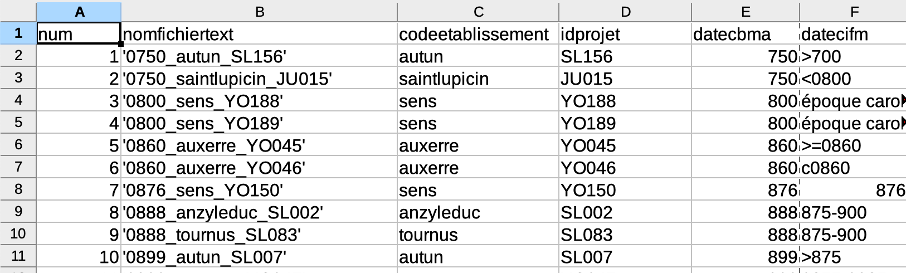

- Extract of a part of the .CSV file with the complete metadata of the corpus of inscriptions.

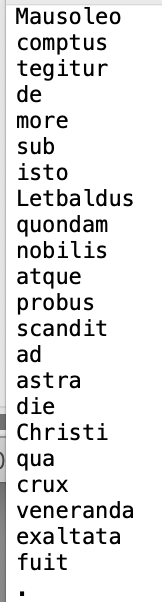

- Tokenization (one line = one word = one token), performed with the OMNIA tokenizer (Renaud Alexandre), which, among other things, also performs a whole series of text harmonizations, such as replacing “j” with “i”, “v” with “u”, separating enclitics (aquarumque = aquarum + que), replacing accented characters, deleting double spaces, etc. (https://glossaria.eu/lemmatisation/#page-content).

- Lemmatization (POS-tagging), with the assignment of a POS (part of speech) to each token, and reconstitution of the file, with the addition of metadata (here, only the file name). The file thus contains, for each word/token (first column), the POS (second column) and the lemma (third column).

Selective bibliography

(in chronological order)

- Schmid H., “Part-of-Speech Tagging with Neural Networks”, Proceedings of the 15th International Conferenceon Computational Linguistics (COLING-94), 1944.

- Delatte L., Évrard É., “Un laboratoire d’analyse statistique des langues anciennes à l’Université de Liège”, L’Antiquité classique, 30-2, 1961, p. 429-444.

- Greeneand B., Rubin G., Automatic grammatical tagging of English.Technical report, Providence, 1971.

- Busa R., “The Annals of Humanities Computing : the Index thomisticus”, Computers and the Humanities, 14, 1980, p. 83-90.

- Guerreau A., “Pourquoi (et comment) l’historien doit-il compter les mots ?”, Histoire & Mesure, 4/1-2 (1989), p. 81-105. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/hism.1989.878

- Bon B., “OMNIA – Outils et Méthodes Numériques pour l’Interrogation et l’Analyse des textes médiolatins”, BUCEMA - Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre, 13, 2009, p. 291-292. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cem/11086

- Longrée D., Poudat C., “Variations langagières et annotation morphosyntaxique du latin classique”, TAL, 50 – n° 2/2009, Special issue on “Natural Language Processing and Ancient Languages”, p. 129-148.

- Bon B., “OMNIA: outils et méthodes numériques pour l’interrogation et l’analyse des textes médiolatins (2)”, BUCEMA - Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre, 14, 2010, p. 251-252. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cem/11566

- Longrée D., Philippart de Foy C., Purnelle G., “Structures phrastiques et analyse automatique des données morphosyntaxiques : le projet LatSynt”, in S. Bolasco, I. Chiari, L. Giuliano (eds), Statistical Analysis of Textual Data, Proceedings of 10th International Conference Journées d’Analyse statistique des Données Textuelles, 9-11 June 2010, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, LED, p. 433-442.

- Longrée D., Poudat C., “New Ways of Lemmatizing and Tagging Classical and post-Classical Latin: the LATLEM project of the LASLA”, in P. Anreiter, M. Kienpointner (éd.), Proceedings of the 15th International Colloquium on Latin Linguistics, (Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft), Innsbruck, 2010, p. 683-694.

- Longrée D., Philippart de Foy C., Purnelle G., “Subordinate clause boundaries and word order in Latin: the contribution of the L.A.S.L.A. syntactic parser project LatSynt”, in P. Anreiter, M. Kienpointner (éd.), Proceedings of the 15th International Colloquium on Latin Linguistics, (Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft), Innsbruck, 2010, p. 673-681.

- Bon B., “OMNIA: outils et méthodes numériques pour l’interrogation et l’analyse des textes médiolatins (3)”, BUCEMA - Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre, 15, 2011, p. 333-334. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cem/12015.

- Guerreau A., “Textes anciens en série”, Bulletin du centre d’études médiévales d’Auxerre, BUCEMA, Collection CBMA, mis en ligne le 01 mars 2012. URL: https://doi.org/10.4000/cem.12177

- Ouvrard Y., Verkerk Ph., “Collatinus, un outil polymorphe pour l’étude du latin”, Archivum Latinitatis Medii Aevi, 72, 2014, p. 305-311.

- Perreaux N., L’écriture du monde. Dynamique, perception, catégorisation du mundus au moyen âge (VIIe - XIIIe siècles). Recherches à partir de bases de données numérisées, thèse de doctorat, Université de Bourgogne, Dijon, 2014. URL: https://shs.hal.science/tel-03084322

- Aouini M., “A NooJ Module for Named Entity Recognition in Middle French Texts”, in J. Monti, M. Silberztein, M. Monteleone, M. Pia di Buono (éd.), Formalising Natural Languages with Nooj 2014, Cambridge, 2015, p. 99-112.

- Eger S., vor der Brück T., Mehler A., “Lexicon-assisted tagging and lemmatization in Latin : A comparison of six taggers and two lemmatization methods”, Proceedings of the 9th SIGHUM Workshop on Language Technology for Cultural Heritage, Social Sciences, and Humanities (LaTeCH), Beijing, 2015, p. 105–113.

- Horsmann T., Erbs N., Zesch T., “Fastor Accurate? A Comparative Evaluation of PoSTagging Models”, Proceedings of the Int. Conference of the German Society for Computational Linguistics and Language Technology, 2015, p.22-30.

- Eger S., Gleim R., Mehler A., “Lemmatization and Morphological Tagging in German and Latin: A comparison and a survey of the state-of-the-art”. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, 2016. URL: http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2016/pdf/656_Paper.pdf

- Kestemont M., De Gussem J., “Integrated Sequence Tagging for Medieval Latin Using Deep Representation Learning”, Journal of Data Mining and Digital Humanities, 2016. URL: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01283083/

- Kestemont M., de Pauw G., van Nie R., Daelemans W., “Lemmatization for variation-rich languages using deep learning”, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 32-4, 2017, p. 797-815. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqw034

- Gągała Ł., “Authorship Attribution with Neural Networks and Multiple Features : Notebook for PAN at CLEF 2018”, in L. Cappellato, N. Ferro, J.-Y. Nie, L. Soulier (éd.) Working Notes of CLEF 2018 - Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum. Avignon, France, September 10-14, 2018. URL: http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2125/paper_146.pdf

- Manjavacas E., Kadar A., Kestemont M., “Improving Lemmatization of Non-Standard Languages with Joint Learning”, arXiv:1903.06939v1, 2019. URL: https://arxiv.org/format/1903.06939v1

- Manjavacas E., Kestemont M., emanjavacas/pie v0.1.3 (Version v0.1.3). Zenodo (2019, January 17). DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2542537

- Clérice T., chartes/deucalion-model-lasla: LASLA Latin Lemmatizer - Alpha (Version 0.0.1). Zenodo (2019, February 1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2554847

- Camps J.-B., Clérice T., Duval F., Ing L., Kanaoka N., Pinche A., “Corpus and Models for Lemmatisation and POS-tagging of Old French”, Journal of Data Mining and Digital Humanities, 2021. URL: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03353125

- Holgado C., Lavrentiev A., Constant M., “Évaluation de méthodes et d’outils pour la lemmatisation automatique du français médiéval”, Traitement Automatique des Langues Naturelles, 2021, Lille, France, p.153-161. URL: https://hal.science/hal-03265897

- Clérice T., Détection d’isotopies par apprentissage profond: l’exemple de la sexualité en latin classique et tardif. Thèse de doctorat, Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3, 2022. URL: https://www.theses.fr/s226893

- Clérice T., Jolivet V., Pilla J., “Building infrastructure for annotating medieval, classical and pre-orthographic languages: the Pyrrha ecosystem”, Digital Humanities, 2022. URL: https://hal.science/hal-03606756v1

- Sommerschield T., Assael Y., Pavlopoulos J., Stefanak V., Senior A., Dyer C., Bodel J., Prag J., Androutsopoulos I., de Freitas N., “Machine Learning for Ancient Languages: A Survey”, Computational Linguistics, 1-44 (2023). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1162/coli_a_00481